1. Stara pjesma

FOTO: Privatni album

Zvonko Bušić vjerovao je kako dobre stvari trebaju biti dostupne svima. Ono za što je živio, radio i vjerovao, za što je podnio žrtvu, objavljeno je u knjizi “Zdravo oko”, koja je dostupna na Amazonu. pod nazivom “All Visible Things”. Taj djelić hrvatske povijesti odsad ćete moći čitati svake druge srijede na hrvatskom i engleskom jeziku, na portalu dijaspora.hr. Poglavlje po poglavlje, kap krvi po kap krvi i život dan po dan u 33 dijela – samo s jednim ciljem! Trajat će…

U noći sa 16. na 17. travnja 1987. pobjegao je hrvatski emigrant Zvonko Bušić iz tamnice Otisville (udaljene oko 100 kilometara od grada New Yorka u istoimenoj državi), ali je nakon 30 sati uhićen i ponovno vraćen u isti zatvor. O tome kako je uspio pobjeći iz jednog od sigurnijih američkih zatvora, ali i što […]

Stara pjesma

Znani i neznani ljudi, rodbina i prijatelji, svi se raspituju, potiču me, nagovaraju, pa i preklinju da napišem memoare, tvrde da moja životna priča ne smije ostati nezapisana. Najuporniji su oni mi najbliži, a i tu prednjači moja Penelopa. Svi moji argumenti kako me je ovih pet godina na slobodi dotuklo i skršilo daleko više negoli trideset i dvije godine zatvora, da sam ostario, umoran i iscrpljen, da sam ja svoju životnu priču živio i da se sada ne mogu u nju uživjeti, da danas ima više onih koji (uglavnom o sebi) pišu knjige nego onih koji ih čitaju, da ja ni po talentu ni po zanimanju nisam pisac i da ne želim loše napisanom knjigom razočarati čitatelje, i da su danas svi prezasićeni svime za njih su bili samo izgovori, izbjegavanje dužnosti i odgovornosti.

Zapravo, oni su imali valjane protuargumente: svaka je povijest, koliko god bila istinita, ipak samo priča; onaj tko dopusti da njegovu priču do kraja ispričaju drugi, ni sam se u toj priči neće prepoznati, pa kako može očekivati da ga prepoznaju oni koji dolaze!? Hrvatska povijest velika je knjiga koja se piše i nadopisuje stoljećima, a ja sam u njoj, bez lažne skromnosti, barem jedan odjeljak ili jedna rečenica.

O tome kako će ta rečenica biti intonirana odlučit će vrijeme koje je pred nama, ali moja je dužnost da sada kada se približavam kraju svoga puta progovorim o vremenu i događajima u kojima sam sudjelovao, isto kao što sam se tada osjećao dužnim i pozvanim u njima djelovati. S tako pomiješanim osjećajima prihvaćam se ovoga posla, pisanja sjećanja, svjestan da je krajnji rezultat prilično neizvjestan, i da ću opisujući sve nevolje i patnje, kojih mi u životu nije nedostajalo, na neki ih način iznova proživjeti.

Knjige koje čitamo u mladosti prate nas do kraja našeg života. U početku kao zabava i strast, kasnije kao sudbina. Još od djetinjstva čitao sam mnogo, halapljivo i strastveno. S jedanaest godina čitao sam Robina Hooda Henryja Gilberta, s trinaest Zločin i kaznu Fjodora Mihajloviča Dostojevskog, s četrnaest zabranjenu i poluzabranjenu političku literaturu. No možda je moj kasniji životni put ponajviše odredio jedan istrgnuti list sa Starom pjesmom Antuna Gustava Matoša. Pjesme nikada nisam učio napamet, ali one koje su u mojoj nutrini pogađale neku srodnu žicu, čitao sam s toliko žara da su mi se urezale u pamćenje i bez nekog posebnog truda.

Strah od mogućeg dolaska stražarskog vozila te trijumfalna radost glede uspješnog bijega toliko me osvojiše da se ni dan-danas ne sjećam kako sam pretrčao onih pedesetak metara od ograde do susjedne šume. Tek kada sam se desetak sekundi odmorio, vidio sam stražarska kola kako promiču pored mjesta gdje sam se ja probio. Nemoguće mi je […]

Pa tako i Matoševa Stara pjesma:

O, ta uska varoš, o ti uski ljudi,

O, taj puk što dnevno veći slijepac biva,

O, te šuplje glave, o, te šuplje grudi,

Pa ta svakidašnja glupa perspektiva!

Čemu iskren razum koji zdravo sudi,

Čemu polet duše i srce koje sniva,

Čemu žar, slobodu i pravdu kada žudi,

Usred kukavica čemu krepost diva?

Među narodima mi Hrvati sada

Jesmo zadnji, robovi bez vlasti,

Osuđeni pasti i propasti bez časti.

Domovino moja, tvoje sunce pada,

Ni umrijeti za te Hrvat snage nema,

Dok nam stranac, majko, tihu propast sprema.

Rekao sam sebi tada: E, ima, ima barem jedan koji će, ako treba, i umrijeti za te, Domovino! Zvučalo je to možda djetinjasto, ta i bio sam još dijete. Ali, danas na pragu starosti pitam se vrijedi li uopće ljudski život ako je u njemu dijete posve umrlo!? Mnoge sam iluzije iz djetinjstva i mladosti usput pogubio, no uza zavjet dan Domovini, stojim i danas bez ostatka.

Međutim, djetinjstvo ima moć da svemu što nas okružuje daje sjaj. U spomenutoj Matoševoj pjesmi zanemario sam razočaranost zrelog čovjeka, skučenost domaćih prilika, „šuplje glave“ i „šuplje grudi“, a perspektive koje su mi otvarale knjige koje sam čitao bile su sve prije nego sive i beznadne. Dječaku se na pragu momaštva junačka smrt za pravu stvar čini sjajnom perspektivom. Ako nije tako, premalo je života u tom dječaku.

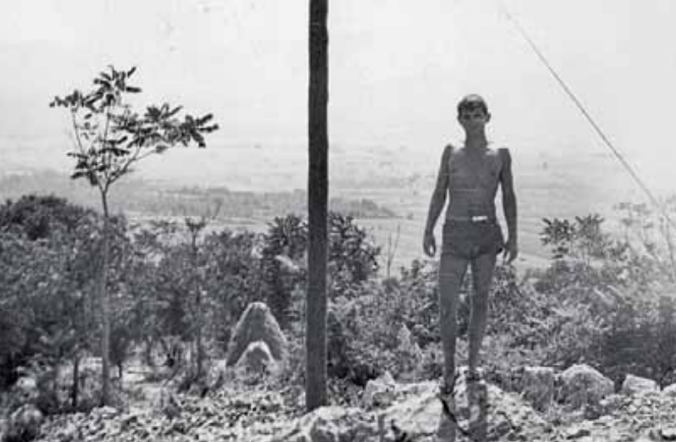

U šesnaestoj sam ostao bez oka, taj me hendikep nikada nije sprječavao da se upuštam i u najluđe vratolomije. S podjednakom strašću kao na čitanje bacao sam se na vožnju biciklom, veranje po najnepristupačnijim mjestima, vesele igre i razne nestašluke. U američkom zatvoru često sam se s nostalgijom prisjećao tih dana, tražio i nalazio u njima snagu da ostanem otvoren prema životu, spašen za nadu. Djetinjstvo, čini mi se, nad ostalim razdobljima života ima prednost da polaže pravo na sve mogućnosti života koje je u stanju zamisliti. U svojoj dječačkoj mašti mogao sam istodobno biti i Robin Hood, i Raskoljnikov koji odustaje od zločina i podiže revoluciju, i Andrijica Šimić i Kendušin mali koji na magarcu tjera sepet smokava na pijacu u Posušje. Iluzija te djetinje svemoći tu i tamo bi se nasukala na sprudove stvarnosti, ali to me ne bi pokolebalo. Nešto slično dogodilo se i u priči o smokvama.

Život stvara autoritete. Oni se ne biraju. Njihov život je put za druge. Taj put za druge je autoritet koji se slijedi! Njihov autoritet dolazi iz njihove snage, a njihova snaga iz njihova Duha. Stoga su spremni na nemoguće, učiniti najviše, prijeći najdalje, izdržati najduže, tražiti moralno najviše, čeznuti za istinom najgorljivije… Takav autoritet ima […]

Naši Posušani, Gornjaci kako smo ih zvali, zbog znatno veće nadmorske visine nisu imali vlastitih smokava. Mati me poslala da otjeram na magarcu nešto smokava i prodam ih na tržnici u Posušju. Kako se u to vrijeme do novca vrlo teško dolazilo, nisam odolio iskušenju. Za novac od prodanih smokava kupio sam si neke sitnice u tamošnjoj trgovini. No trebalo se vratiti kući. Plan koji sam smislio činio mi se genijalnim. Vidio sam na pijaci neke žene kako prodaju krumpire. Kući sam se u Goricu vraćao prečicom, baš kraj brojnih krumpirišta. Svako malo bih zastao i iskopao štapom po koju cimu, vadio krumpire i tovario ih na magare. Nastojao sam da to bude s više različitih njiva kako nikoga ne bih previše oštetio. Kući sam se vratio s krumpirima umjesto s novcima za prodane smokve. Majci sam rekao da sam zamijenio smokve za krumpire. Ona me samo prodorno pogledala, malo prebirala po krumpirima pa prijekorno zavrtjela glavom: „Zvonko, nisu ti ovo krumpiri s pijace, vidi se da nisu s iste njive! Priznaj da si ih iskopao usput dok si se vraćao!“

Desetak godina kasnije kad sam u Beču pripovijedao o tome Benjaminu Toliću, on me u šali optuži da su to pretežno bili krumpiri s njive njegova djeda. Nije bilo druge, morao sam platiti bocu vina. Ali nije mi žao, uz tu litru čuo sam i priču o tome kako je Benjamin u ljutnji na djeda posjekao djedovu šljivu. Lijepa je to priča i vrijedila je i cijele demižane, a kamoli litre vina. Ipak, ostavljam je za kasnije, a sad se opet vraćam djetinjstvu.

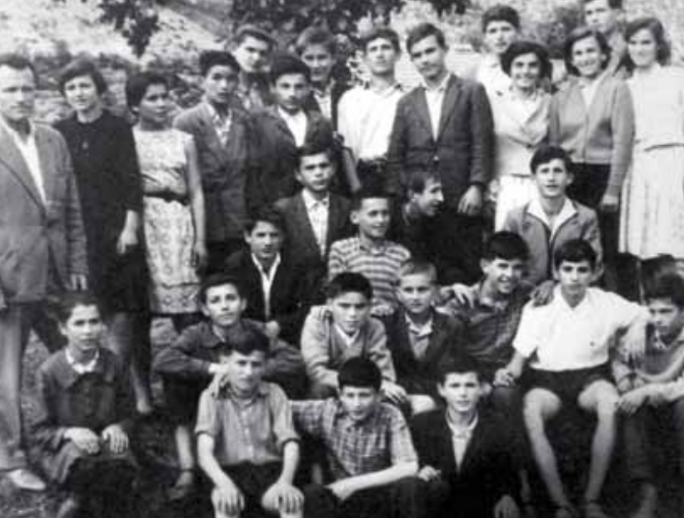

Prva četiri razreda osnovne škole pohađao sam u rodnoj Gorici. Kasnije sam trebao nastaviti osmogodišnju školu u Sovićima. Međutim, nekolicina nas skovala je čvrst plan da u peti razred krenemo u Imotski, premda je Imotski bio dvostruko udaljeniji. Otac i majka nisu se toliko protivili mojoj odluci koliko se moglo očekivati s obzirom na nelogičnost moga izbora. Vjerojatno sam i kao dječak imao prilično razvijenu moć uvjeravanja. U zatvoru su me zbog toga zvali „filozof“ i često tražili da posredujem u raznim razmiricama među zatvorenicima. Majka je samo praktično primijetila da će mi trebati trostruko više obuće za svakodnevno pješačenje do Imotskog, nego što bi mi trebalo za pješačenje do Sovića. I tako sam peti i šesti razred išao u Imotski.

To mi se tada činilo kao dvostruka prednost. Prvo, išao sam u školu u tadašnjoj Federativnoj Republici Hrvatskoj, gdje su profesori ipak bili pretežno Hrvati i gdje se nije pisalo ćirilicom, dok je u školama u Bosni i Hercegovini, pa tako i onoj u Sovićima, jednu školsku zadaću bilo obvezno pisati ćirilicom, jednu latinicom. Drugo, u imotsku gimnaziju išao je moj stariji brat, a i Bruno Bušić, koji je već tada nama mlađima bio svojevrsni uzor. Bruno je prvi put bio zatvoren već 1957., i njegov put hrvatskog buntovnika i revolucionara bio je, čini mi se, već tada zacrtan. A i moj.

Na samom početku ove ispovijesti stoga želim čitatelju objasniti svoju poziciju i razloge zašto sam se već u ranoj mladosti zanosio idejama o hrvatskoj borbi za slobodu. I zašto je, uostalom, spomenuta Matoševa pjesma tako snažno djelovala na mene. Još kao dijete slušao sam od starijih što su sve proživljavali u Drugome svjetskom ratu i koliko je mladih ljudi iz moga kraja bilo ubijeno nakon rata. Zapažao sam i sȃm kakav se teror provodio nad stanovništvom u mome i okolnim selima. Jugokomunistički režim doveo je svoje ljude u naše krajeve. Učitelji i nastavnici u školama bili su pretežito Srbijanci ili Crnogorci, tako se u školama nametao srpski jezik i ćirilica. Milicajce su također doveli iz Srbije da teroriziraju domaće stanovništvo. Kao dijete gledao sam kako poreznici odnose sve što su ljudi krvavo stekli i privrijedili svojim radom. Ljudi su iz dana u dan živjeli u strahu.

Kao dijete nisam mogao razumjeti taj strah i u meni se rađao bunt protiv takve nepravde i eksploatacije. S velikim zanimanjem slušao sam zastrašujuće priče o tome što su sve ljudi doživjeli, a i vlastitim sam očima imao prilike gledati teror koji se u svakom vidu provodio nad stanovništvom mojega kraja. Sjećam se tako jednog slučaja kada su poreznici u pratnji naoružanih milicajaca odveli jedinu kravu roditeljima jednog mog vršnjaka. Imali su sedmero djece. Djeca su plakala i valjala se u prašini jer im je bilo žao krave koja ih je hranila, majka je kukala, molila i obećavala kako će kasnije platiti porez, ali sve je bilo uzalud. Istina, bilo je i domaćih izroda koji su sudjelovali u provođenju terora i zastrašivanja, no oni su samo bili oruđe u rukama stranih okupatora. Sve je to u meni stvaralo sve jači bunt, osjećao sam užasnu nepravdu. U meni se već tada formirao izoštren osjećaj za to što je to pravda, a što nepravda.

Mlad i nemoćan tražio sam način kako služiti pravdi i pomoći napaćenom narodu kojemu sam i sam pripadao. Bilo mi je neshvatljivo da se nije smjelo naglas ni spomenuti hrvatsko ime, kao da nas je netko nevidljivom kistom jednostavno izbrisao. To me posebno čudilo i vrijeđalo kada sam čitajući i slušajući priče upoznao tragičnu povijesti našega hrvatskog naroda. S obzirom da sam po prirodi bio nemiran duh, buntovnik i slobodnjak, pustolov i romantik, a najviše idealist, bilo mi je predodređeno krenuti na neizvjestan i opasan put borbe za oslobađanje svoje domovine. Za mene tada ništa nije bilo prirodnije nego posvetiti svoj život idealima hrvatske slobode i ispravljanju nepravde.

Tada još nisam razumio nikakvu ideologiju, samo ideologiju pravde. Kako sam odrastao, slušao sam da ima i drugih i starijih od mene koji su se žrtvovali za istu stvar, a neke sam od njih, naravno, i susretao pa smo u tajnosti razgovarali i zanosili se idejama kako pomoći oslobodilačkim idejama i akcijama. Još u gimnaziji uspijevao sam dolaziti do nekih povijesnih knjiga i čitati o znamenitim Hrvatima koji su se borili za samostalnost i slobodu hrvatskog naroda. Osim toga, mene su još kao dijete nadahnjivale epske pjesme o našim junacima koji su se borili protiv Turaka, poput znamenitih hajduka i uskoka, Zrinskih i Frankopana, a posebno me pak nadahnjivala Kvaternikova Rakovička buna.

Gledajući iz današnje perspektive te moje mladenačke zanose, a nakon što sam pročitao brojne knjige povjesničara različitih naroda i civilizacija, te podosta filozofskih i političkih pisaca i uz to dosta toga iskusio i na vlastitoj koži, mogu reći da sam ponosan što sam se u ranoj mladosti zauzeo takve političke stavove. Kao što je prirodno da se čovjek brine o svojoj obitelji, isto je tako prirodno brinuti se o stanju i budućnost vlastitog naroda. Jednostavno, narod je proširena obitelj.

Bratovština sv. Stjepana Prvomučenika Gorica-Sovići i Matica hrvatska Ogranak Grude organizirali su petu humanitarnu Likovnu koloniju u čast i znak zahvalnosti za svu žrtvu tamnice i uzništva hrvatskom vitezu i domoljubu Zvonku Bušiću Taiku. Likovna kolonija održana je od 1. do 4. rujna 2021. u Taikovoj rodnoj Gorici. Ovu humanitarnu akciju podržalo je Ministarstvo hrvatskih […]

Kada se to tako izravno kaže, možda djeluje previše simplificirano, no bitne istine ljudskog života i položaja u svijetu, držim, treba uvijek nastojati izreći jednostavno i jasno. Samo se tada uz njih može čvrsto stajati, braniti ih i vjerovati u njih. Posvemašnji relativizam i sofističko izmotavanje, tako popularni u suvremenom svijetu, znaci su duboke krize koja potresa našu civilizaciju. Očito je da je riječ prije svega o filozofskoj i misaonoj krizi koja se onda, kako vidimo, pretače i u druga područja života kao što su politika, gospodarstvo, moral.

Zvonko Bušić

EN

Zvonko believed that good things should be shared with everyone. What he lived, worked for and believed in, what he sacrificed for, is presented in his book “All Visible Things”, which is available on Amazon. From now on, you will be able to have access to this part of Croatian history every other Wednesday and print it out free of charge, in Croatian and English, on the dijaspora.hr portal. Chapter by chapter, drop of blood by drop of blood, and life day by day in 33 parts – with only one goal! He will live on…

An Old Poem

People I know and people I don’t – relatives, friends, and all others – are all asking, encouraging, persuading, even begging me to write my memoirs, saying my life story must not be left untold. The most persistent are those closest to me, most of all my Penelope. All my arguments – that these five years in “freedom” have exhausted and drained me much more than my thirty-two years in prison, that I am too old, tired, and used up, that I lived my life story and have no need to live it again, that today there are more people writing (mostly about themselves) than reading books, that I am not a writer either by talent or occupation and don’t wish to produce a poorly written book, thus disappointing the readers, that everyone is overloaded with everything today – all this people consider mere excuses, a dereliction of my duties and obligations.

Actually, they have valid counter-arguments: every history, no matter how accurate, is just a story; if you allow someone else to tell your story to the end, you won’t even recognize yourself, so how do you expect those who come after you to recognize you? Croatian history is a long story that has been written and expanded upon for centuries, and I am a part of it, without false modesty, if only just a paragraph or a single sentence. How that sentence will be interpreted, time will tell, but it is my duty, as I approach the end of my journey on earth, to speak about the times and events in which I participated, just as I felt obligated back then to engage in them. So it is with mixed feelings that I have taken on this task, the writing of my memoirs, conscious of the fact that the end result is uncertain, and that, describing all the agony and suffering I experienced – no small amount – I will be forced to live through it all a second time.

The books we read in our youth accompany us to the end of our lives. In the beginning as entertainment and adventure, and later as Destiny. From early childhood, I read constantly, voraciously, and passionately. At the age of eleven, I read Robin Hood by Henry Gilbert; at thirteen, Crime and Punishment by Dostoyevsky; and at fourteen, prohibited and partially prohibited political literature. But my later path in life was perhaps most determined by a torn-out page containing Antun Gustav Matos’ “Old Poem”. I had never consciously tried to memorize poems, but the ones that struck some chord within me I read with so much emotion that they seared themselves into my memory without my even trying. That’s what happened with Matos’ “Old Poem”:

Oh this narrow town, these narrow-minded people,

Oh this crowd blinded more and more every day,

Oh these empty heads, oh these barren souls,

And this meaningless perspective!

What good is a rightly reasoning man

What serves the enthusiasm of a soul and mind that dreams,

What good is flight of imagination longing for freedom and justice

Among cowards?

What good the virtue of a giant?

Of all nations, we the Croats are now the last,

Slaves without power,

Destined to perish and disappear in disgrace.

Oh, my homeland, your sun is now setting,

While Croats have not even strength enough to die for Thee

While strangers, o my Mother,

Quietly prepare our destruction!

I told myself back then: oh yes there is, there is at least one person who would die for you if necessary, my dear homeland! It may sound childish, but after all, I was a child. However, today, in the later stages of life, I ask myself whether human life has any value at all if the child within has died? I’ve lost many of my childhood illusions but I still stand today, without hesitation, by the oath I gave to my homeland.

Meanwhile, childhood has the power to cast a glow on one’s surroundings. In the aforementioned Matos poem, I put aside the disappointment of the mature man, the restrictiveness of conditions here, the “empty heads”, and the “barren souls”; the perspectives that allowed me to access the books I read were anything but gray and hopeless. To a boy on the verge of manhood, a heroic death for the “right cause” seemed a magnificent prospect. If it were not so, then there was too little life in the boy! At the age of sixteen, I lost an eye, but this handicap never prevented me from engaging in any number of crazy stunts. I applied the same degree of passion I had for books into learning to ride a bicycle, scaling the most inaccessible locations, and inventing all sorts of games and pranks. In prison, I often recalled these days with nostalgia, finding in them the strength to remain open toward life and still harbor hope. It seems to me that childhood, more than any other period in life, has an advantage in that it gives you the right to imagine all the possibilities within your power. In my childish imagination I could at the same time be Robin Hood, and Raskolnikov, who gives up crime and raises a revolution, and Andrijica Simic (Note: a hajduk or outlaw from Herzegovina who fought against Turkish rule in the mid-19th century. He stole from the wealthy and gave to the poor peasants. Pursued for years and eventually caught, Simic was sentenced to life imprisonment. He was the motif of many literary, lyrical, and other works of art), as well as Kendusha’s little son driving a load of figs on his donkey to the Posusje marketplace. Childish illusions of omnipotence sometimes ran up against the shoals of reality, but that did not deter me. Something similar happened in a story about figs.

People from Posusje, the “mountain people”as we called them, were unable to grow their own figs due to the region’s higher altitude. My mother had me take a load on the donkey to sell at the market there. Since money was hard to come by back then, I succumbed to temptation. For the money I got from selling the figs, I bought some small items at a local store. But I still had to return home. What to do? The plan I came up with seemed brilliant to me. At the marketplace, I’d noticed women selling potatoes. I returned home to Gorica taking a shortcut that passed by several potato fields. From each one, I’d dig out a few potatoes with a stick and load them onto the donkey. I made sure to take them from several fields so that nobody would notice the loss. Thus I returned home with potatoes instead of money for the figs I’d sold. I told my mother what I’d done. She gave me a penetrating look as she picked over the potatoes, and then in a reproachful tone said: “Zvonko, these potatoes aren’t from the marketplace! I can see they’re all from different fields. Now admit that you dug them up on your way back home!”

Ten years later in Vienna, when I confessed this to a friend, Benjamin Tolic, he accused me of having taken them from his grandfather’s field. I had no choice but to stand him a bottle of wine. But I didn’t regret it, because in return for the wine I got the story of how Benjamin, angry at his grandfather, cut down his plum tree. It was a nice story and was worth a whole barrel of wine – not just a bottle. But I’ll leave that for later and return now to my childhood.

I attended the first four years of elementary school in Gorica. Later I was to continue the next eight years in Sovici. Meanwhile, several of us devised a plan to continue on to the fifth grade in Imotski, even though it was twice as far to walk. My mother and father didn’t protest all that much, in spite of the irrationality of my decision. Apparently, my powers of persuasion, even as a child, were fairly well-developed. Because of this, I was called “Philosopher” in prison and often asked to mediate in various disputes among the prisoners. My mother simply made the reasonable comment that I would need three times as much footwear in order to walk to Imotski every day instead of Sovici. At any rate, I attended fifth and sixth grades in Imotski. This seemed to me to be a double advantage. First, I went to school in the then Federal Republic of Croatia, where the professors were mostly Croatians and where the Cyrillic alphabet was not used, while the schools in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and even the one in Sovici, required that half the homework be written in Cyrillic and half in the Latin alphabet. Second, my older brother, as well as Bruno Busic, who was already a paragon to us younger ones, attended the Imotski high school. Bruno had been imprisoned for the first time in 1957, and his path as a Croatian rebel and revolutionary had already been circumscribed, it seems, back then. And mine as well.

At the beginning of these memoirs, I would like to explain my position to the readers and the reasons I supported these ideas on the struggle for Croatian freedom in the early years of my youth. And why, in addition, the poem by Matos had such a strong effect on me. As a child, I listened to what my elders experienced in the Second World War and heard how many young people from my area had been killed after the war. I myself experienced the type of terror perpetrated on the people of my area and neighboring villages. The Yugoslav Communist occupiers “imported” their people into our territories. Teachers and professors were mostly Serbs or Montenegrins, so that the Serbian language and alphabet were imposed upon us. The police were also brought in from Serbia to terrorize the local populations. As a child, I myself witnessed the tax inspectors confiscating everything a family had so painfully and exhaustively worked for with their bare hands. People lived in daily fear. As a child, I simply couldn’t come to terms with this fear, and a rebellion rose within me against the injustice and exploitation. I was transfixed by the horrible stories I heard, what all these people experienced, and saw also with my own eyes the horror perpetrated on the people in my area. I recall one instance when the tax inspectors, accompanied by armed soldiers, confiscated the only cow of a school friend’s parents. They had seven children. The children were crying and throwing themselves on the ground, because it was their only cow and fed all of them. Their mother was wailing, beseeching the soldiers, promising to pay the taxes later, but to no avail. And even worse, these were actually local people who participated in this terror and repression, but they were really only tools in the hands of the foreign occupiers. This all created an ever-stronger rebellion within me, a greater and greater feeling of injustice. Even then, I had formed a strong sense of what was and was not just.

Young and powerless, I searched for a means to serve justice and help the suffering nation to which I belonged. It was incomprehensible to me that we were not even allowed to speak the Croatian name aloud, as though someone had simply erased us with an invisible brush. I was especially amazed and insulted after I became familiar– through constant reading and listening– with the tragic history of my Croatian people. Because I was by nature a restless soul, a rebel, adventurer and romantic, but mostly an idealist, I was somehow predetermined to embark upon an uncertain and dangerous path in the struggle for the freedom of my homeland. Nothing was more natural to me than to dedicate my life to the ideals of Croatian freedom and righting injustice. I had no understanding then of any ideologies except the ideology of justice. So I grew up listening to how others older than myself had made sacrifices for the same cause, and some of them, of course, I met personally, and discussed with them which actions and ideas would best accomplish our goal of independence. In high school, I’d already succeeded in getting my hands on certain history books, where I read about significant Croatians who had fought for freedom and independence.

Besides that, I was inspired as a child by the epic poems about our heroes who had fought against the Turks, such as the famous Zrinski and Frankopan and Andrijica Simic, and I was especially impressed by the Rakovicka uprising in 1871 (Note: led by Croatian politician Eugen Kvaternik against authorities of Austria-Hungary, with the aim of establishing an independent Croatian state at the time when it was part of Austria-Hungary.)

Looking at my youthful exuberance from today’s perspective – after all the history books I read about different nations and civilizations, all the philosophers and historians, and after experiencing quite a lot firsthand – I can say that I take pride in the political positions I adopted in my early youth. Just as it is normal to care for one’s family, it is just as normal to care for the state and future of one’s own nation. Simply put, a nation is an extended family. When expressed like this, it might seem too simplified, but I believe we should always try to express the essential truths of humankind and its position in the world simply and clearly. Only then can we stand firmly behind them, believe in them, and defend them. The omnipresent relativism and sophistic acrobatics so popular in the world today are signs of the deep crisis shaking our civilization. It’s obviously a philosophical crisis that has spilled over into other areas of life, such as politics, economy, and morality.

Zvonko Bušić